|

||||

| Vertebrates> Jibal Ghuzayma | ||||

|

|

||||

| From:

Jordan Times - Weekender Article by: Ammar Khammash |

||||

|

||||

|

With us, Dr Ahmad Smadi, from the Natural Resources

Authority, along others from the NRA, picked up the fossil hunting

fever. Many field trips were made, often to the most God-forsaken

areas, scanning the escarpment overlooking Wadi Rum from the north,

and, later on, looking in the areas to the northeast of Jafr. In geology,

every bit of information ads up to the enrichment off the bigger picture;

a layered picture where hundreds of millions of years are compressed

as a record of rock. Looking for dinosaurs requires understanding

the geological formations so well that one starts reconstructing a

mental image of the landscape and the habitat where dinosaurs would

have lived. With every new evidence this "paleo-environment"

becomes clearer. One also develops the skills of reading the landscape

and integrating to it the relevant insights from geological maps and

reports resulting in an on-going cycle of research in Amman and field

trips to the desert. We were basically looking for areas that revealed

fossil wood, within the Cretaceous period (144- 65 million years ago),

for that would be the ideal habitat of dinosaurs, in wooded lands

by the side of lakes, or at shorelines. More and more specimens of

plant fossils were found, in areas that reports never mention any

flora in them. Trunks as big as 50 cm across were found in Wadi al

Dab'i, to the south of Harraneh Fort, and slowly we started following

this layer further east to find great exposures of it in east of Azraq

and in another location extremely rich in fossils: the area of Jibal

Ghuzayma halfway between Bayer and Jafr. Not all field trips had all of us; I've developed

the habit of sneak solo expeditions, on Saturdays, where I was looking

west of the concrete Azraq-Jafr road finding ammonites, fossil-trees,

fish, and tiny bone fragments and no dinosaurs. Few months ago, Dr Ahmad A. Samdi and Mr. Hassan

Abu Azzam conducted several days of fieldwork in the part of Jibal

Ghuzayma to the east of the cement road. Dr Samdi's knowledge of geological

layers is fortified by his specialization in micropaleontology, branch

of science often considered the backbone of figuring out age sequence

of sedimentary rocks. They followed the layer with trees and ammonites,

and under a cliff cut by winter waterfalls they spotted some peculiar

rock. There were large bone fragments, protruding out of rocks freshly

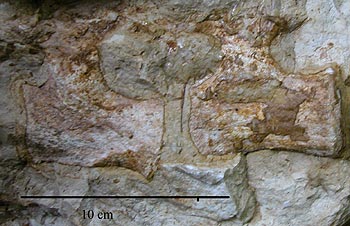

exposed after collapsing from the side of the cliff. Bones within this sedimentation of the 'Mowaqqar

Chalk-Marl Formation' are almost always found in round layered rocks

geologists call concretions. Often bones are jumbled-up, mixing different

parts of the animal skeleton together, and, possibly, with those from

other animals, of the same or different species, and with fragments

of invertebrates such as baculites (strait ammonite/ squid-related

mollusks) and other shelled marine animals.

Reading fossil bones is not easy; scientists

often spend months or even years preparing and reconstructing bone

fragments, making physical or virtual reconstruction, to understand

their function and their relation to other known skeletal remains

of the same geological period. This is the work of a vertebrate paleontologist

such as Mr. Iyad Zalmout. After initial inspection of the find Mr. Iyad

Zalmout could identify the bones as part of a dinosaur, related to

the long-necked 'Sauropods'. The largest bone fragment was part of

the sacrum (pelvic girdle); other bones included some vertebra of

the tail, tibia (leg-bone below the knee) and axis (neck-bone joining

the skull). These skeletal fragments of a dinosaur, which would have measures 12-14 meters in length, are very likely to add to science a new dinosaur species. Out of the hundreds of different species of dinosaurs, the majority were identified from only small skeletal fragments often much less that what we have; furthermore, some species were only identified by their footprints. It is also important to note that this was one of the last dinosaurs to live, as just above the layer where the specimen was discovered, the line of mass-extinction (so far most scientists relate to the catastrophic meteor impact in the Gulf of Mexico) marks the end of the Cretaceous Period, at its very last Maestrichtian Stage, ending about 65.4 million years ago. The issue here is that time was very vast and

evolution kept coming up with endless varieties; all what we know

about animals from the deep past is constructed from such finds, fragments

that represent the very lucky animal parts that had the rare chance

to turn into fossils. For Jordan, this is an important specimen,

if further studies confirm that it belongs to a new species of dinosaurs,

and then it might be given the name 'Jordanosaur' or 'Arabiasaur'.

The specimens might also become the early core of a Jordanian Natural

History Museum project, to house other fragments from other locations

found by others. For us, and for our children, to relate to the Jordanian landscape there is nothing stronger than such a find. These fragments should be given registration numbers as part of a national registry system, they should be made available to science, and most importantly they should not end up outside the country, like many other specimens found in Jordan before.

1- Escarpment of Jibal

Ghuzayma, with chalk concretions containing bone fragments and marine

shelled animals. In this layer, parts of a skeleton of a dinosaur

were discovered. |

||||

|

To avoid commercial exploitation, the exact location can be given only for scientific purposes. Copyright © 2002-2004 Pella Museum. All rights reserved. |

||||